This post was first published on May 30, 2012.

As we have previously reported, both the Houses of the Parliament passed the Copyright Amendment Bill 2012 in quick succession with overwhelming support from the opposition. The Bill is now awaiting the President’s assent and a gazette notification to become a law. The Bill has undergone many changes based on the recommendations of the Standing Committee and offers a scheme of provisions different from its previous version (the Bill 2010) in many respects.

Here is an attempt to analyse the new Copyright Amendment Bill 2012 with its possible impact on the entertainment industry. For the purposes of discussion, let us consider the example of a movie (cinematograph film). A cinematograph film embodies literary works such as the script and lyrics, musical works such as the composition of songs and background score, artistic works such as the sets, graphics etc., and performances by the artists such as actors, singers, dancers, and stuntmen. Sound Recordings are created out of the lyrics, composition and performances and the same in incorporated in the film.

A. Section 17 (Commissioned Works and Works under Contract of Employment)

According to Section 17 of the original Act, the author is the first owner of copyrights in a work unless such work is commissioned by another person or is created under a contract of service or employment, in which cases the employer or the person commissioning the work is the owner. A new proviso has been added to the section providing that the logic or notion of commissioned work or work created under employment does not accord ownership to the employer where such work is incorporated in a cinematograph film. Therefore, a production house will not own the copyrights created by its employees during the course of their employment. Even where a previously commissioned work is used in a cinematograph film, there is a reversion of rights to its author. Surprisingly, this provision does not apply to works incorporated in a ‘sound recording’ and therefore, a record label can still own the works created by its employees or commissioned authors.

B. Section 18 (Assignment of Copyrights)

Under the original Copyright Act, author of a literary, artistic or musical work could assign the copyright to the producers for incorporation in a film. Such assignment could broadly be for both current and future modes of exploitation. There was no right to receive any royalty for exploitation of the works. Where such right existed, it could be transferred or waived. The amendment has added three new proviso to Section 18:

First, an assignment made to a producer or other person is not applicable to any medium or mode of exploitation that is not in existence at the time of the assignment unless specifically mentioned in the assignment agreement;

Secondly, the author of a literary or musical work incorporated in a cinematograph film cannot assign or wave his right to receive ‘equal share of royalties’ from the ‘assignee’ for utilisation of such work in any form other than communication to the public in a cinema hall. The only exceptions are copyright societies and legal heirs to whom an author may assign the right. Therefore, producers should now share the non theatrical exploitation royalties equally with the script writers, lyricists and composers;

Thirdly, the author of a literary or musical work incorporated in a sound recording shall not assign or waive his right to receive equal share of royalties from the ‘assignee’ for utilisation of such work in any form. The permitted exceptions are copyright societies and legal heirs to whom an author may assign the right.

Though, this amendment comes with a noble intention of granting royalty rights to the authors, the language of the amendment is so ambiguous and general that it leads to more questions than answers. What is meant by ‘equal share of royalty from exploitation of works’ is not clear. There are no objective criteria to determine the share of royalty accrued from the lyrics of a three minute song, in a 90 minute long film. Secondly, the royalty sharing principle is unfairly extended to any form of exploitation of the full film other than theatrical exploitation. It seriously undermines the copyright of the Producer in the cinematograph film. The television serials, programs, music album videos, telefilms etc. that qualify to be a cinematograph film have been neglected in the amendment. Such films have to share equal royalties with the authors even for their primary exploitation on television.

Further, unlike Hollywood, in the Indian films, the lyricist/composer derives inspiration from the script and the plot of the film. Their works are influenced by factors such as the lead actors of the film, the situation in the film etc. The director and producer have considerable inputs on the final outcome of the film and the songs. Considering the fundamental differences, comparison with the western system of revenue sharing seems grossly unfair.

C. Section 19 (Mode of Assignment of Copyright)

Three new clauses (Clauses 8, 9 and 10) are added into Section 19 of the Act that provides for the mode of assignment.

Clause 8 declares that any assignment made contrary to an assignment made to a copyright society is void. Therefore, once an author assigns all his present and future rights to a copyright society, he cannot assign the same to other persons or exclude a future work from this general assignment. Clause 9 contemplates that no assignment made for utilisation a work in a cinematograph film shall affect the right to claim equal royalty for any exploitation of the work other than as part of the cinematograph film screened in a cinema hall and Clause 10 incorporates similar provision with respect to a sound recording; Even if a composer or lyricist is not a member of any society and assigns all rights in the work to the producer, he will still be eligible to receive equal share of royalty accruing from non theatrical exploitation of his work as part of the film or otherwise.

These clauses are applied mutatis mutandis to the provisions relating to ‘License’ (that is to say, an author cannot grant a license contrary to his assignment to the society or a license granted by an author does not affect his right to claim equal share of royalties from non-theatrical exploitation).

D. Section 33 (Copyright Societies)

As per the current law, no person other than a copyright society can be in the business of issuing licenses over works in which copyright subsists. Only recognised exception is that the owner of the rights can issue licenses with respect to his works. With the Amendment, even the owner of a literary, dramatic or musical works incorporated in a cinematograph film should issue licenses for exploitation of such works only through a copyright society. Further the registration of a copyright society is made valid for five years and is renewable thereon.

E. Statutory Licenses

i. Cover Versions: Newly added Section 31 C provides that any person willing to make a cover version in the form of a sound recording of any literary dramatic or musical work where sound recording of that work is already made by the author or under the author’s license, may do so by giving a prior notice of his intention, providing advance copies of all covers and advance payment of royalties to the owner. The cover recording shall not be different from the original medium of recording unless such medium has become obsolete. No alteration to the original work is permitted in the cover version.

ii. Statutory License for broadcasting of Literary and musical work and sound recording: Newly added Section 31D allows broadcasting organisations to communicate to the public by way of broadcast or performance of a published work (literary and musical work, sound recording and not a cinematograph film) by giving a notice in the prescribed manner and advance payment of royalty prescribed by the copyright board. The rates shall be separate for television and radio broadcasting. This provision will not affect the agreements concluded before the amendment. Therefore, the copyright owners in the sound recordings have to spend more on monitoring all these channels to ensure that the logs being provided to them are accurate.

F. Sections 38A and 38B (Performers’ Rights)

These provisions are newly added to consolidate and provide certain economic rights and moral rights to the performers. Once a performer has consented incorporation of his performance in a cinematograph film, the performers’ rights (not moral rights) can be enjoyed by the producer. However, a performer is entitled to performance royalty where ‘the performances are made for commercial use’.

Further, the provisions relating to the assignment of copyrights are made applicable mutatis mutandis to the performers’ rights. Therefore, a performer cannot assign his rights on his performance contrary to his agreement with a society (which may come into existence after the commencement of the amendment) and no assignment of performance will affect a performer’s rights to receive equal share of royalties from the non theatrical exploitation of the performance as part of the film or from any exploitation of the sound recording.

G. Other Provisions

There are a number of other provisions that are amended to provide clarity and to consolidate the current law. The definition of ‘Performer’ has been modified to exclude incidental performances. Section 14 has been added to provide digital storage of a cinematograph film, sound recording and other works as a separate copyright. ‘Commercial Rental’ has been defined to exclude non profit libraries. The provisions relating to compulsory licenses for the benefit of the disabled, extension of the term of copyrights in photographs, Digital Rights Management provisions come with noble intentions. The proposal of making the ‘principal director’ as a co-author of the cinematograph film has been dropped following the standing committee report on the ground that the ‘time was not ripe’! For whatever that means, it certainly is a sigh of relief for the producers.

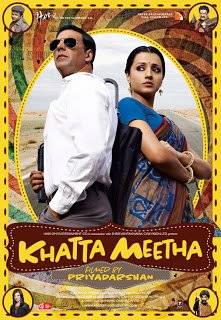

Image from here