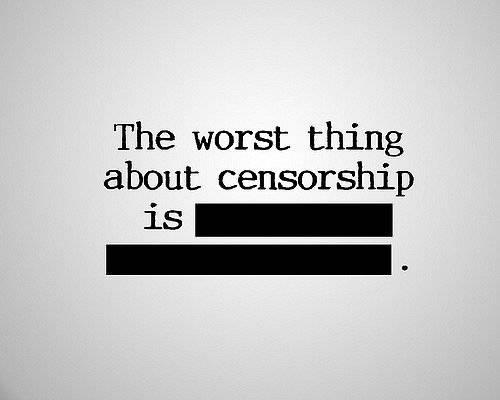

Expression in the form of films is unique and special in many ways. Films merge life-like moving pictures, sounds, and other effects to tell a story, or send a message unlike any other form of expression. When the film is shown to a captive audience in a closed, dark environment, with the aid of advanced technology, its impact is heightened substantially. It is believed that one does not experience the same euphoria, emotion and engagement if the same film is seen on a television or computer at home. The impact of the film is therefore presumed to be higher when seen in theaters and other closed, captive environments.

While talking about the impact of films on the minds of people, the Supreme Court[1] said:

“It is no doubt true that the motion picture is a powerful instrument with a much stronger impact on the visual and aural sense of the spectator than any other medium of communication; likewise, it is also true that the television, the range of which has vastly developed in our country in the past few years, now reaches out to the remotest corners of the country catering to the not so sophisticated, literacy or educated masses of people living in distant villages. But the argument overlooks that the potency of the motion picture is as much for good as for evil. If some senses of violence, some nuance of expression or some events in the film can stir up certain feelings in the spectator, an equally deep strong, lasting and beneficial impression can be conveyed by scenes revealing the machinations of selfish interests, scenes depicting mutual respect and tolerance, scenes showing comradeship, help and kindness which transcend the barriers of religion. …”

Since the evolution of cinematograph technology, law makers, courts and jurists were of the opinion that films have the ability to impact minds of the people unlike any other form of expression. Owing to their ability to influence and impact human minds, public exhibition of films was and continues to be, conditioned on prior review and certification. The objective of such a review and certification before permitting exhibition is to restrain film expression in the interests of sovereignty, public order, decency, morality, and other reasons, and to limit detrimental effects of such expression on the public. Aware that expression in the form of cinematographic films is within the scope of fundamental right to freedom of speech and expression, which cannot be diluted unless the consequences are detrimental to national, public or social interest, Courts have time and again held that any imposition of restrictions must normally be reasonable, and must fit into the permissible limitations that may be placed on the expression under the constitution.[2]

The Cinematographic Act, 1952, (“Act”) provides circumstances under which restrictions may be placed while certifying films for exhibition. The Central Board of Film Certification (“CBFC”) constituted under the Act has been given the task of reviewing and examining films to certify them as U (Universal Viewing), U/A (Parental Guidance), A (Adult Viewing only), and S (restricted viewing), or reject a certificate if it is unfit for public exhibition.[3] The certificate is issued or rejected after the film is reviewed by an examining body, and sometimes, a revising body of CBFC. While issuing the certificate the CBFC may require excisions (“cuts”) or modifications to the film.[4] The said cuts are normally requested based on principles and guidelines laid down under the Act and Rules framed thereunder. The decision of the CBFC is appealable to the Film Certification Appellate Tribunal (“FCAT”), or may be challenged before the High Court or Supreme Court under the writ jurisdiction.[5] While reviewing films, the CBFC follows the Act, Rules framed thereunder and the Guidelines issued by the Central Government.[6]

Authored by Dr. Kalyan C. Kankanala, Senior Partner and Chief IP Attorney, Banana IP Counsels. The author can be reached at kalyan@bananaip.com

References

[1]Ramesh.S/O Chotalal Dalal vs Union Of India & Ors, 1988 AIR 775, 1988 SCR (2)1011

[2] Article 19(1)(a) and 19 (2), Constitution of India; S. Rangarajan Etc vs P. Jagjivan Ram,1989 SCR (2) 204, 1989 SCC (2) 574; Ramesh.S/O Chotalal Dalal vs Union Of India & Ors, 1988 AIR 775, 1988 SCR (2)1011

[3] Section 5A of Cinematograph Act, 1952: 1 [(1) If, after examining a film or having it examined in the prescribed manner, the Board considers that- (a) the film is suitable for unrestricted public exhibition, or as the case may be, for unrestricted public exhibition with an endorsement of the nature mentioned in the proviso to clause (i) of sub-section (1) of section 4, it shall grant to the person applying for a certificate in respect of the film a “U” certificate or, as the case may be, a “UA” certificate, or (b) the film is not suitable for unrestricted public exhibition, but is suitable for public exhibition restricted to adults or, as the case may be, is suitable for public exhibition restricted to members of any profession or any class of persons, it shall grant to the person applying for a certificate in respect of the film an “A” certificate or, as the case may be, a “S” certificate; and cause the film to be so marked in the prescribed manner: Provided that the applicant for the certificate, any distributor or exhibitor or any other person to whom the rights in the film have passed shall not be liable for punishment under any law relating to obscenity in respect of any matter contained in the film for which certificate has been granted under clause (a) or clause (b).]

[4] Section 5 B of Cinematograph Act, 1952: (1) A film shall not be certified for public exhibition if, in the opinion of the authority competent to grant the certificate, the film or any part of it is against the interests of 1 [the sovereignty and integrity of India] the security of the State, friendly relations with foreign States, public order, decency or morality, or involves defamation or contempt of court or is likely to incite the commission of any offence. (2) Subject to the provisions contained in sub-section (1), the Central Government may issue such directions as it may think fit setting out the principles which shall guide the authority competent to grant certificates under this Act in sanctioning films for public exhibition.

[5] Section 5 C of Cinematograph Act, 1952: (1) Any person applying for a certificate in respect of a film who is aggrieved by any order of the Board- (a) refusing to grant a certificate; or (b) granting only an “A” certificate; or (c) granting only a “S” certificate; or (d) granting only a “UA” certificate; or (e) directing the applicant to carry out any excisions or modifications, may, within thirty days from the date of such order, prefer an appeal to the Tribunal: Provided that the Tribunal may, if it is satisfied that the appellant was prevented by sufficient cause from filing the appeal within the aforesaid period of thirty days, allow such appeal to be admitted within a further period of thirty days. (2) Every appeal under this section shall be made by a petition in writing and shall be accompanied by a brief statement of the reasons for the order appealed against where such statement has been furnished to the appellant and by such fees, not exceeding rupees one thousand, as may be prescribed.

[6]The principles for guidance in certifying films issued under Section 5 B(2) of the Cinematograph Act, 1952, available at http://cbfcindia.gov.in/html/uniquepage.aspx?unique_page_id=1, last visited on 23.03.2017.

Image source / attribution here.

Image is governed under creative commons attribution CC BY-SA 2.0